The Japanese government and nuclear power plant operators have long grappled with how to dispose of spent fuel and other high-level radioactive waste. Authorities finally settled on the approach of burying waste deep underground at facilities 300 or more meters below the surface. In 2002, NUMO, the Nuclear Waste Management Organization of Japan, began hunting for a storage location by inviting municipalities to put themselves forward as candidate sites. To date, this “volunteer” policy has netted only three participants, the towns of Suttsu and Kamoenai in Hokkaidō and Genkai in Saga.

On November 22, Numo presented a report on the effects of its bibliographic studies for the two municipalities of Hokkaidō, which were introduced in November 2020, and concluded that the studies can go to the current level in Sutttsu and part of the southern end of Kamoenai .

Suttsu, a small coastal community of some 2,600 people situated in the southwest of Hokkaidō around 140 kilometers to the west of the capital of Sapporo, boasts rich fisheries and was the first municipality in Japan to host an onshore windfarm. Kamoenai, a town of around 800, sets in the southeastern corner of the Shakotan Peninsula about an hour’s drive north of Suttsu and is famed for its catches of sea urchin, scallops, and squid. Both towns are roughly the same distance from the Tomari Nuclear Power Plant, the only nuclear power station on the northernmost of Japan’s four main islands, and like many other rural areas in Japan, they face the dual demographic crunch of an aging and declining population.

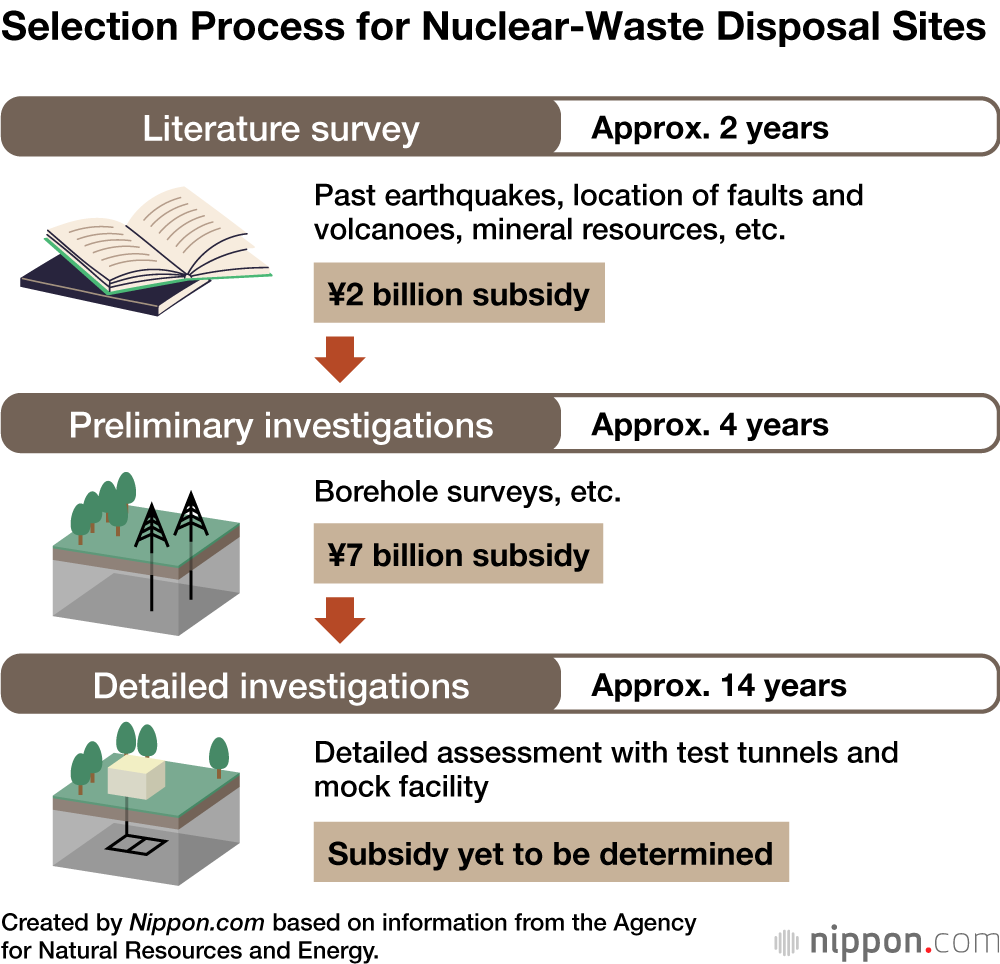

The first step in the three -step review procedure of the government to decide in a elimination site is a table investigation that occurs to geological data studies and studies on the history of local volcanic and seismic activity, having finished this, having finished Suttsu and Kamoenai were in transparent. To continue with the phase for the moment, an initial investigation that includes geological exploration and drilling surveys. The final step in the variety of the site is a detailed investigation of underground geology control tunnels and other techniques. The Government provides a subsidy of 2 billion yen for the municipalities participating in the literature survey and some other 7 billion yen for the drilling survey. The subsidy for the third level of the procedure has not yet been decided.

Local governments will have to give their consent for the review procedure to move to the stage for now, and Suttsu Mayor Kataoka Haruo has expressed his goal of holding a referendum on the issue, a technique that Kamoenai Mayor , Takahashi Masayauki, says he is also considering.

Kataoka says he offered Suttsu for the literature survey as a way to start the discussion about nuclear waste. “We’re going to have to have it somewhere in Japan,” he said. “It’s a fact that we all want to reconcile. ” Looking back, however, he admits that Revel In left him with mixed feelings. Although it forced citizens to face the elimination factor, it also provoked an unforeseen amount of anger. “I never imagined that a small town like ours placing your hand would be the target of so much vitriol. “

Taking to social media and other online platforms, opponents of Suttsu’s move unleashed a rain of abuse, with some calling the town “a disgrace to Hokkaidō” and others vowing to shun its seafood and other products. Much of the anger was directed at city hall, including a rash of telephone calls and irate messages faxed to municipal departments.

Nishimura Nagisa, who as head of the Suttsu Tourism and Local Products Association manages its social media presence, had the unpleasant task of compiling the smear. The avalanche of negative messages sent shivers down his spine. “The comments were almost all unpleasant. “

From the start of the documentary studies, Hokkaidō Governor Suzuki Naomichi voiced his opposition, saying that NUMO and the central government “mainly threw cash in the face. “The 4 neighboring towns and villages of Suttsu and Kamoenai also expressed their discomfort, certain that they point to themselves as “denuclearized” and others publicly oppose nuclear waste across their borders, which many as an attempt to identify a blockade. The tone in the media also has a tendency to be negative, editorialists who write articles that criticize the polls.

Documentary studies accompanied through projects aimed at informing citizens about the process. These included 17 discussion sessions, data and examine meetings, as well as a stop at the nuclear fuel reprocessing facility at Rokkosho, in Aomori Prefecture.

Tanaka Noriyuki, who runs an electronics store in Suttsu, credits those efforts over the past four years with raising local awareness of the nuclear waste problem. “That brought the challenge to light,” he says. “After all, we all gain benefits from nuclear energy, so I believe that no organization has the strength to oppose the investigation procedure or a discussion about what to do with this waste. “

In the other spectrum end they are citizens like Echizen’ya Yoshiki, who opposes research. A member of the Suttsu City Council challenged Kataoka in 2021, operating on a platform for completing an investigation. Mayor, continues to speak, arguing that the resolution to allow the investigation of the literature to move forward was premature. “The structure of a waste elimination center will have long -range implications for the city,” he says. “The resolution to obtain began the investigation after informing citizens well, and only with their consent. “

Other residents echo his concerns, with many lamenting that it is no longer possible to calmly discuss the matter. “It’s important to that we talk about nuclear waste,” says Echizen’ya. “But it has become a sore spot for the community.”

Every country reliant on nuclear power faces the long process of hashing out what to do with high-level radioactive waste that will remain hazardous for tens of thousands of years to come. Japan has opted for a “volunteer first” approach that includes the government offering subsidies to woo municipalities. One expert attributes this line of action to the fraught history of Japan’s nuclear power industry, saying that “the government faced major opposition every step of the way when building its fleet of nuclear power plants and wants to avoid heading down that rocky path again.”

The Ministry of Economy, Commerce and Industry and Numo organized more than one hundred information sessions throughout the country, but the number of municipalities that have been presented to participate in the selection procedure of sites remains three.

Kataoka attriyetes The little reaction to the voluntary aspect of the investigations and the government is not more proactive in its technique. “The Central Government says that candidate sites need to be located, but it is a half-hearted effort,” he said. “Mayors, after all, are reluctant to raise their hands if it means compromising their selection bids. ” He argues that a more direct technique is necessary, with the government directly inviting 10 or more applicants in the country to participate in surveys.

It also suggests expanding the amount of the subsidy for participation in the documentary survey. Suttsu used the 2 billion yen to build housing for nurses running in the city, as well as other infrastructure projects, while Kamoenai invested much of its cash into renovating its port. Kataoka, however, insists that the amount fits the burden placed on the municipalities, stating that “we have used the much-needed budget wisely, but 2 billion yen is only scant praise for this. ” that we have experienced.

Unlike Suttsu, the study of literature caused little controversy in Kamoenai. Mayor Takahashi stresses that for the village and other places located near nuclear power plants, it is imperative to participate in the process of locating a permanent storage site. But at the same time, citizens want to be informed about the pros and cons of this issue. “I hope to lay the groundwork for future generations to learn how to proceed. “»

He laments the paucity of municipalities interested in participating in site selection research, which he attributes to the current approach. “I think to stoke debate on the issue, the government will have to put forward several candidate sites of its choice.”

Even if the Numo declares Suttsu and Kamoenai eligible for the current level of investigations, the consent of the governor and the local legislative bodies to proceed is required, which is not guaranteed.

In reaction to the release of the NUMO report, Governor Suzuki said he was opposed to initial investigations in the moment stage. The reactions of the local assemblies of Suttsu and Kamoenai were not explicitly opposite, leaving room for continued debate yet keeping up a reserved position. An official from the Hokkaido prefectural government summed up the existing scenario as bleak: “Considering that the governors of other prefectures come ahead in favor of the investigations, the government will have to come up with a new plan. “

Even if local and regional governments are in favor of continuing the investigations so far, there is still a possibility that the initial investigation will reveal that the sites are geologically unsuitable for storing high-level nuclear waste. Experts point out, for example, that Suttsu is near a fault and that a volcano looms near Kamoenai. Above them, weak and brittle rock strata crisscross the region. Together, they cast a long shadow over the government’s strategy. hopes of locating a site.

In its search for a permanent place of expulsion, Japan can be encouraged through Finland. The Nordic country is a world leader in nuclear garages with its onkalo facility. The site, located on the island of Olkiluoto, off the western coast of Finland, was chosen in 2000 from among a hundred communities that submitted to host the garage installation. The variety procedure marked a peak of engagement with citizens to gain public trust.

Japan currently has 19,000 tons of spent fuel rods in temporary storage at nuclear power plants. Mixing the material with molten glass, a process known as vitrification, to create a stable form, will produce 2,530 canisters of waste. This number jumps to 27,000 canisters when unprocessed nuclear waste is included, and experts advise that any permanent disposal facility will need to be able to store over 40,000 canisters. Japan’s current roadmap has a facility opening sometime between 2033 and 2037, but at the current rate of progress, it is highly unlikely that authorities will meet this timeline.

A growing group of experts considers the current site variety procedure moribund and is calling on the government to reconsider its approach. Suzuki Tatsujirō, a professor of nuclear engineering at Nagasaki University and former vice chairman of Japan’s Atomic Energy Commission, says that if the 3 sites that sign up for the investigation procedure are “remarkable,” he argues that the Volunteering policy “places too much burden on the leaders of small regional governments. It suggests that the government adopt a new course of action by appointing an independent organisation to propose between 50 and a hundred sites and offer projects to inform and engage local actors at each level of the examination procedure.

Professor Emeritus Imada Takatoshi of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, who headed the Science Council of Japan’s advisory committee on nuclear waste, asserts that the disposal debate needs to take place with the willful understanding of the immense timeline spanning tens of thousands of years. “We need to earnestly consider how our decisions now will be seen by future generations. I hope that with a national debate involving stakeholders at all levels we can forge a path forward.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Wind turbines rotate along the coast of Suttsu, which is an early adopter of onshore wind power generation. © Matsumoto sōichi. )