Later this week, China will embark on the world’s second trip to the far side of the Moon. The goal is to collect the first rocks from the interior of the South Pole Aitken Basin (SPA), the largest and oldest crater-affecting rocks on the lunar surface, and bring them back to Earth for analysis.

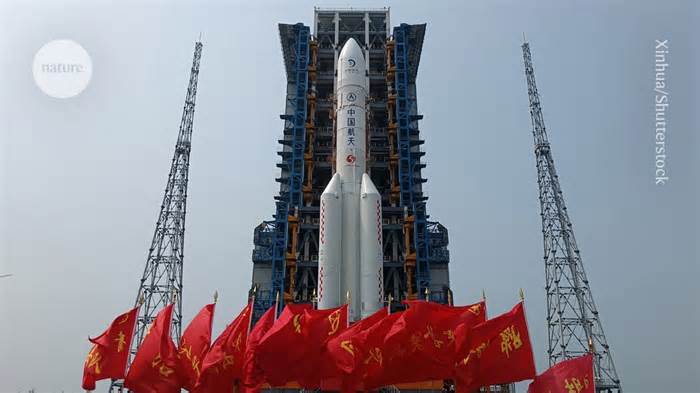

A stack of 4 spacecraft to carry out this unprecedented and highly complicated mission, known as Chang’e-6, is now placed on the tip of a five- and seven-meter-tall Long March Five rocket, which has been waiting for liftoff since its launch. of the Wenchang satellite. Center on Hainan Island in southern China.

“The total procedure is very risky,” says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

But he believes it is a threat worth facing: “The samples from the SPA basin would be very interesting from a scientific point of view and would teach us a lot about the history of the Moon and the beginnings of the solar formula. “

Because the Moon is tidally blocked on Earth, humans have only been able to see its visual appearance for thousands of years. In 1959, the first photographs of the far side of the Moon sent through the Soviet Luna 3 probe revealed a face dotted with mountains and have an effect on craters, in contrast to the relatively elegant nearby appearance. Since then, scientists have been collecting data from satellites orbiting the Moon to perceive its little-known other half. In 2019, China’s Chang’e-4 has to become the first spacecraft to soft-land and conduct studies on the far side of the Moon.

The upcoming Chang’e-6 mission, with its landing site carefully selected among Chinese scientists and foreign colleagues, aims to provide the first precise measurements of the age and composition of the geology of the far side of the Moon. This can provide key clues as to why the two aspects of the Moon are so different (the so-called mystery of the lunar dichotomy) and test theories about the early history of the solar system.

The SPA basin is a large indentation at the bottom of the opposite side, about 2,500 kilometers wide and 8 kilometers deep. In the northeastern part, Li’s team identified three possible landing zones. The sites may contain a variety of tissues formed during repeated asteroid impacts and volcanic eruptions over two billion years and may therefore be scientifically rich.

The most likely rock to be collected is basalt, a dark-colored, cooled lava, which has already been brought back to Earth for study from the near side of the Moon. With the first basalt samples from the far side, scientists will then conduct comparative studies to understand why volcanic activities occurred on a much smaller scale and ended up much earlier on the far side of the Moon,” says Long Xiao, a planetary scientist at the China University of Geosciences in Wuhan.

Calculating the age of the SPA basin would also be a major achievement, says planetary geologist Carolyn van der Bogert of the University of Münster, Germany. This will help settle the long-standing debate over whether the formula for the Moon and the inner Sun were the same as the Moon’s inner Sun. If the SPA basin were older, the theory of extensive bombardment would be called into question.

In addition to the basalts, scientists hope Chang’e-6 will also recover fragments of other rocks scattered during influencing events. If the Chinese project collides with material ejected from the crust or the deeper lunar mantle, it will turn into clinical gold.

Chang’e-6 was originally built as a backup for the Chang’e-5 project, which aimed to bring back 1. 73 kilograms of samples from the near side of the Moon in 2020. Because the two spacecraft are identical, the number of sites for the Chang’e-6 landing was limited to latitudes similar to Chang’e-5 and required a flat surface, says Chunlai Li, deputy lead designer of the project at the National Astronomical Observatories in Beijing.

Like its predecessor, Chang’e-6 does not predetermine its landing site, but will use its tools in the descent procedure to locate the safest and most favorable location. “Chang’e-6’s landing would be more complicated than Chang’e’s. e-5 simply because the landing site on the other side is more rugged,” Xiao says.

Chang’e-6, like its twin, is composed of an orbiter, a lander, an ascender, and a re-entry module. When the spacecraft reaches the Moon, it will split into two parts, with the lander and ascender heading toward the lunar surface while the orbiter and re-entry module will remain in orbit.

If it manages to make the complicated and comfortable landing, the lander will drill and collect two kilograms of soil and rock. The sampling procedure should be completed within 48 hours, after which the ascender should take off from the lander and return to the lunar orbiter. There it is expected to dock and transfer the valuable samples to the re-entry module for the return trip.

During pattern collection and liftoff from the lunar surface, the Chang’e-6 lander will not be able to communicate directly with Earth. Each command will have to pass through a relay satellite called Queqiao-2. Launched last month and now operating in a highly elliptical orbit around the Moon, Queqiao-2 is more rugged than the Queqiao satellite that served on the Chang’e-4 mission. Its 4. 2-meter umbrella-shaped antenna has the ability to service up to ten spacecraft on the far side of the Moon. the moon.

Chang’e-6 also carries clinical payloads from France, Sweden, Italy and Pakistan. The Detection of Degassed RadoN (DORN), which will be the first French tool on the Moon, plans to use radon released through the lunar surface as a tracer. the origin and dynamics of the weak lunar atmosphere. Pierre-Yves Meslin, a planetary scientist at the Institute for Research in Astrophysics and Planetology in Toulouse, France, says previous spacecraft have measured the motion of radon from orbit, but surface-level radon data is the missing piece of the puzzle.

Negative Ions on the Lunar Surface, a payload developed in Sweden with investment from the European Space Agency, will seek to answer the question of why negative ions have not yet been detected on the lunar surface. Negative debris can have a short life and forms either through atoms on the surface that strip electrons from the solar wind, or through molecules that break apart under high-energy solar radiation. The biggest challenge for this tool is overheating, as it has to face the sun, says Neil Melville, ESA’s task manager. But he claims that one hour of operation will be enough to collect the data.

The Italian National Institute of Nuclear Physics sends a laser retroreflector to measure distances. And Pakistan has its first lunar satellite on the Chang’e 6 orbiter, which will be deployed after entering lunar orbit.

The two surface teams will need to complete their work and send the data back to Earth within 48 hours. “Once the samples take off, the ascender will bring with it the communication and formula it has with the lander. The lander tools continue to collect knowledge, there’s no way to get it here on Earth,” Li says.

He says that, like the Chang’e-5 samples, the returned Chang’e-6 samples will be shared with the community.

“When those samples return to Earth, they will be like a Christmas present: whoever opens them will be pleasantly surprised,” says Bogert.

It’s me: https://doi. org/10. 1038/d41586-024-01056-x

News 25 Apr 24

Article 24 APRIL 24

News & Views 24 Apr 24

Existing Questions and Occasions 30 April 24

News 25 Apr 24

News 24 Apr 24

Correspondence 30 April 24

Article 24 APRIL 24

Article 24 APRIL 24