Supported by

By Michael Forsythe and Gabriel J. X. Dance

Jerry Yu has the trappings of what the Chinese call second-generation rich. He boasts a Connecticut prep-school education. He lives in a Manhattan condominium bought for $8 million from Jeffrey R. Immelt, the former General Electric chief executive. And he is the majority owner of a Bitcoin mine in Texas, acquired last year for more than $6 million.

Yu, a 23-year-old student at New York University, has also unknowingly become a case study in how Chinese citizens can move cash from China to the United States without attracting the attention of authorities in either country.

The Texas facility, a giant knowledge center, didn’t buy in dollars. Instead, he bought with a cryptocurrency, which provides anonymity, and the transaction is routed through an offshore exchange, preventing anyone from knowing the source of the funding.

Such secrecy allows Chinese investors to access the U. S. banking formula and consequent oversight by federal regulators, as well as circumvent Chinese restrictions on cash leaving China. In a more classic transaction, a bank receiving the budget would know where it came from and would be required by law to report any suspicious activity to the U. S. Treasury.

None of this would have been known if Mr. Yu (BitRush Inc. , also known as BytesRush) hadn’t stumbled upon some disorder in the small region of the Texas Panhandle, the town of Channing, which has a population of 281, where contractors say they have not paid him for all of his work. Your work is mine there.

A wave of lawsuits over the paintings has rocked documents shedding light on transactions that are not made public, as Chinese investors have flocked to the United States, spending hundreds of millions of dollars to build or operate cryptocurrency mines, after the Chinese government banned such operations in 2021.

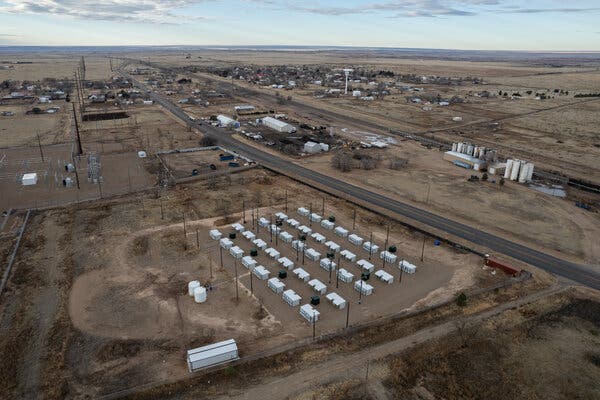

Mining is a way for Chinese investors to generate cryptocurrencies, basically Bitcoin, which they can exchange for U. S. dollars. The Channing mine, built in an open field, is made up of several dozen buildings designed to house 6,000 specialized computers that can work day and night. to guess the correct series of numbers to win new Bitcoins, with a current price of over $40,000 each. These sites can be a burden on the country’s network of forces, the New York Times reported, and their Chinese ownership has attracted national security scrutiny.

In one of the lawsuits involving Mr. Yu, who is a Chinese citizen and a resident of the United States, Texas-based Crypton Mining Solutions alleges that investors in Channing’s mine “are only Chinese nationals, but citizens in highly political and influential business positions. “

The suit offers no conclusive evidence of those ties, and the public money trail ends at Binance, a cryptocurrency exchange. By using a cryptocurrency called Tether and routing it through Binance’s offshore exchange, Mr. Yu’s investors made it impossible to know the source of the funds. At the time of the transaction, Binance’s offshore operations were not adhering to American banking rules, according to the U.S. government.

Last month, Binance pleaded guilty to violating anti-cash laundering regulations and agreed to pay more than $4. 3 billion in fines and forfeitures. At the center of the federal case is Binance’s failure to comply with laws, adding the Bank Secrecy Act, which requires lenders to determine customer identities and report suspicious cash transfers.

Yu referred his questions to Gavin Clarkson, BitRush’s attorney, who said in an email that the company “complies with all required federal, state, and local laws and regulations, adding banking legislation and regulations. “He said Crypton’s claims and added that borrowed at the mine were not being repaid, they were “baseless and unfounded. “

“We owe BitRush money, not the other way around,” he said. In a lawsuit against Crypton, BitRush alleges “gross negligence” and is awarded $750,000 in compensation.

In Channing, the arrival of BitRush last year attracted a lot of attention, with some citizens getting jobs for the mine’s structure, which was built next to an electrical substation.

One of them, Brent Loudder, is a judge, volunteer city fire leader and husband of the county sheriff’s deputy. Loudder, who oversaw electrical and plumbing work for Crypton, said contractors were paid when they protested through work stoppages. An electrical contractor, Panhandle Line Service, is also embroiled in a lawsuit and countersuit with BitRush for overpayment.

Documents shared with the Times through Crypton’s lawyer, David Huang, reveal how BitRush planned to buy the Texas site: the seller, Outlaw Mining, would get $6. 33 million worth of Tether. Using Tether, valued at $1, provides the anonymity of other cryptocurrencies without the volatility of the value of some of them. The purchase contract specified a wallet address (a 42-character alphanumeric series) where the budget would go.

Records indicated that $5,077,000 was owed at the close, and transaction records to be released publicly show that the wallet, registered with a cryptocurrency brokerage firm called FalconX, accepted $5,077,146 worth of Tether at the same time last year. The documents claim that $500,000 worth of Tether has already been paid as a deposit, and the remaining $750,000 will be paid (also to be paid in Tether) after BitRush took possession of the site’s equipment, supplies, and hardware.

However, the source of the quote was publicly recorded and is known only to Binance, the exchange that processed the transaction. The agreement never specifically specified who would make the payment, and Clarkson said BitRush never sent or earned cash through Binance.

FalconX “had no visibility into the origin of the funds,” Purvi Maniar, deputy general counsel for the company, said in a statement. “This illustrates why it is increasingly vital for centralized intermediaries in crypto to be regulated.”

It’s a challenge posed through teams analyzing blockchain, a virtual ledger that records cryptocurrency transfers. “Once the budget is sent to a centralized service on the blockchain, it can no longer be traced back to the user who sent them to that legal exchange process,” such as as a court order, said Madeleine Kennedy, a spokeswoman for Chainalysis, a company that tracks crypto transactions.

Jessica Jung, a spokesperson for Binance, said that crypto wallets on 3 Binance accounts sent Tether invoices and that they were all owned by foreign nationals who were not U. S. residents. U. S. ” Binance. com doesn’t have or serve U. S. customers,” he said. It wrote in an email, adding that it implements “rigorous” procedures to determine the identity of customers.

Paying with Tether is prevalent in the Bitcoin mining industry. An Arkansas miner said he used Tether to buy specialized computers made through a Chinese company for millions of dollars. Another Wyoming miner said he did the same. One of the benefits of those transactions can be sales taxes and capital gains.

A document shared through Huang revealed some of BitRush’s shareholders at the time of Channing’s purchase. After Mr. Yu, the most prominent investor in IMO Ventures, a China-focused venture capital firm founded in San Mateo, California. Another shareholder known in the document as “Lao Yu”, which can be translated as “Old Yu. “

The other two people who signed the loan documents for M. ‘s apartment. Yu in Manhattan, Yu Hao and Sun Xiaoying, fit the names of a married couple in China who own stakes in corporations valued at more than $100 million, according to WireScreen records. A company that provides Chinese business intelligence. A user named Sun Xiaoying is also listed as the director of BitRush.

Clarkson, Mr. Yu’s attorney, did not verify the identity of BitRush’s shareholders or Mr. Yu’s possible relationship to one of them.

Outlaw Mining founder Josey Parks said in a phone call that he couldn’t comment on his monetary arrangement with BitRush because he was bound through a non-disclosure agreement.

“Jerry is a student in the US with a very wealthy circle of family, from what I’m told,” Mr Parks said in a text message. “I don’t know any of his investors or any relationships with foreign entities. “

Alain Delaquérière contributed to the research.

Michael Forsythe is a reporter on the investigations team. He was previously a correspondent in Hong Kong, covering the intersection of money and politics in China. He has also worked at Bloomberg News and is a United States Navy veteran. More about Michael Forsythe

Gabriel J. X. Dance is the Associate Research Writer. His reports focus on the nexus between privacy and security and have led to congressional and criminal investigations. Learn more about Gabriel J. X. Danse

Advertising