n n n ‘. concat(e. i18n. t(“search. voice. recognition_retry”),’n

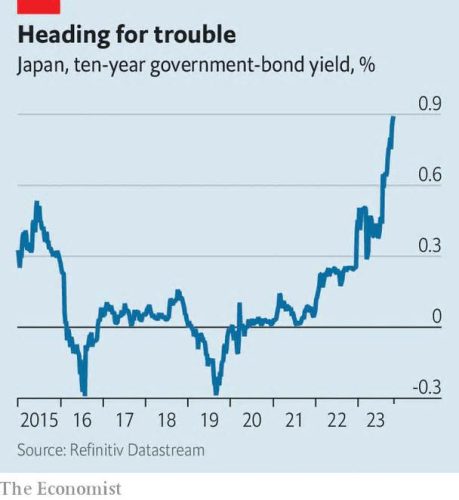

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) failed to offer a mystery for Halloween. Although central banks in other countries have raised interest rates in recent years, the Bank of Japan has stuck to its ultra-loose policy, designed to breathe life into growth. The interest rate is -0. 1%, where it has been for more than seven years. And on October 31, despite mounting pressure, the bank simply adjusted the ceiling on 10-year government bond yields. The 1% cap on yields, which the bank buys massively in bonds to defend, is now a benchmark rather than a rule. In fact, benchmark bond yields are at 0. 95%, their highest level in more than a decade (see chart).

Following the Bank of Japan’s announcement, the yen fell to ¥151, in line with the dollar, its lowest point in decades. Inflation, which has been quiet for a long time, is no longer so low: the Bank of Japan has raised its forecast for “core” inflation for the next 3 years. Many analysts expect the central bank to finish its yield curve control policy early next year and have raised interest rates through April. But even when the BoJ nonetheless raises interest rates, it will most likely do so. It will be only a fraction of a consistent percentage point, meaning that the spread between Japanese bond yields and those of the rest of the world will remain wide, with major consequences for the global monetary sector. A scare is in sight.

To understand why, consider the effect of Japan’s historically low interest rates and ongoing interventions to lower bond yields. Low domestic rates have generated demand for foreign assets as investors seek higher yields. Last year, Japan’s overseas investment source of income was $269 billion more than that generated through foreign investors in Japan, the world’s largest surplus, equivalent to 6% of Japan’s GDP. The huge spread between bond yields in Japan and the rest of the world now poses risks for Japanese investors. that have bought foreign bonds and global issuers that have benefited from the Japanese custom.

The danger is evident in Japan’s largest monetary companies, which invest heavily overseas. The accusation of hedging foreign investments on the difference between the short-term interest rates of the two currencies involved. Short-term interest rates are more than five percentage points higher than Japan’s, and the spread exceeds the 4. 8% yield on 10-year U. S. government bonds. This means that Japanese buyers now incur a guaranteed loss by buying long-term dollar bonds and hedging. That’s why the country’s life insurers, which are among the institutions most involved in hedging its currency risk, sold 11. 4 trillion yen ($87 billion) worth of foreign bonds last year.

The huge spread between short-term interest rates means that Japanese investors now have more limited options. The first is to continue buying abroad, albeit at a higher risk. Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance and Sumitomo Life, which each owned more than 40 trillion yen. In assets last year, they say they will increase their purchases of foreign bonds without hedging against sudden currency fluctuations, betting well against a sudden rise in the yen. Life insurance corporations are conservative, but the longer the massive spread between interest rates persists, the more incentive they will have to take risks.

At the same time, long-term emerging market Japanese bond yields, which are likely to rise further if the Bank of Japan relinquishes control of the yield curve, would potentially prompt local investors to bring their cash home. Japanese 40-year bonds will offer yields of 2. 1%, enough to sustain investors’ capital even if the Bank of Japan hits its 2% inflation target. Westpac’s Martin Whetton said the prospect worries U. S. and European companies and governments, which are accustomed to Japan’s voracious appetite for bonds.

In such a scenario, a source of demand would become a source of investment stress for Western corporations and governments. The yen could appreciate at that point as Japanese investors sell their foreign-currency debt and make new investments in their country. JPMorgan Asset Management’s Bob Michele warns of a decade of capital repatriation.

Japan’s capital flow to the rest of the world, which emerged after a decade of accommodative economic policy around the world, appears likely to decline. Whether the consequences are felt through local economic institutions, or through foreign bond issuers, or both, will become increasingly difficult. more transparent in the coming months. What is already transparent is that this will be felt through someone.

For more expert research on the most important economic, monetary, and market news, sign up for Money Talks, our subscriber-only weekly newsletter.

© 2023 The Economist Limited newspaper. All rights reserved.

From The Economist, license published. The original content can be viewed on https://www. economist. com/finance-and-activity/2023/11/02/how-japan-poses-a-threat-to-the-global-financial-system