Advertising

Supported by

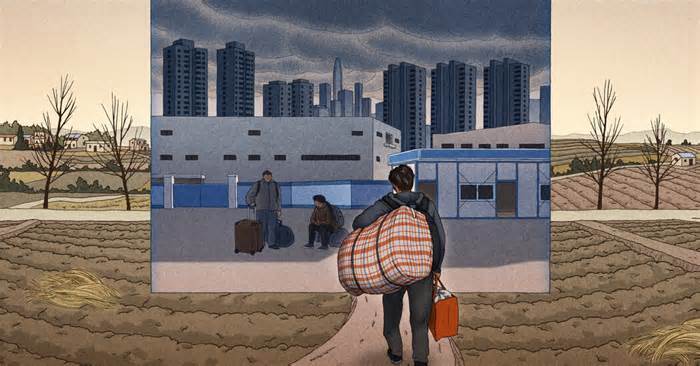

The New New World

Migrant workers, who moved from Chinese villages to cities, were a secret weapon for the progress of the economy. Today, many see few options.

By Li Yuan

When Zhang left his village in northeastern China a decade ago to work as a welder in a big city, jobs abounded. He earned about $50 a day and managed to save as much as possible.

But this year, he still hasn’t found a job as a welder. After moving to the southern city of Guangzhou in March, her only salary, about $820 for 40 days, came from promoting weight-loss products on a social media app. . I had to answer questions from visitors at all hours. Today, he doesn’t paint anything and has no savings. You’ll pay $55 a month in rent for a small studio, but you earn ten cents each. In the morning we chatted and he said he ate a bowl of instant noodles, one of the two foods he eats a day.

Things wouldn’t be much better in his village. Zhang’s circle of relatives grows corn on a small plot of land, earning about $200 a year. His grandparents, both 74, are still farmers; Each receives a pension of less than $15 a month. His father is a migrant worker in Pékin. Su mother, who is unemployed, is looking for work.

At 28, Mr. Zhang, who asked me to use only his surname, is not married and does not plan to have children. “I don’t dare think too much about the future,” he said. “I just need to make some money to stay alive. “He said he would return home soon if he couldn’t find work.

Immigrants have for years been the secret weapon of China’s economic rise. They left their villages to go to big cities to make a living and send cash home, even if it meant running long hours, living in cramped dormitories, and rarely seeing loved ones.

They built China’s skyscrapers, highways, and high-speed rail lines, even though some senior officials referred to them as the “low-end population. “Their reasonable wages have helped China, the world’s largest manufacturer, and rocked the country’s megacities.

Now, when times are tough and it’s harder to find a job, China’s 300 million immigrant employees, who enjoy fragile social benefits, have little to depend on. They don’t get the same fitness, unemployment, and retirement benefits insurance as the city. inhabitants, no matter how thin their safety net. Once migrant staff pass the maximum age for work, they are expected to return to their home villages so as not to be a burden on cities.

Migrant workers are among the most vulnerable groups facing China’s economic slowdown, as jobs in real estate and infrastructure structures are harder to find. Xi Jinping, China’s most sensible leader, admitted in a 2020 speech: “When the economy fluctuates, the first organization that is affected is the migrant workforce. “

He said more than 20 million migrant workers, unable to find work, returned to their villages during the 2008 financial crisis. In 2020, he said, nearly 30 million migrant workers had to stay home and out of work because of the pandemic.

It is difficult to assess the impact of existing disorders on migrant workers. The national unemployment rate, calculated by the National Bureau of Statistics, only takes into account urban unemployment, which stands at just over five percent and is believed to be considered underestimated. The average source of income consistent with the month of migrant staff was $630 in 2022, less than the source of income of those applying for government. And this knowledge is flawed because it only includes the months in which an employee is employed.

Xi said in his speech that the great return of migrant personnel in 2008 and 2020 caused social unrest because “they have land and houses in their villages so they can return to domesticate the land, have food and paintings on something.

But the prospect of returning to the villages is bleak, even frightening, especially for young migrant workers who have spent their adult lives in the city. They can see what’s in store for them. Your parents and grandparents may want to paint until they are no longer physically able to do so and are reluctant to seek medical attention. They don’t normally receive unemployment benefits and can’t rely on their families, as some urban youth do, because their parents’ and grandparents’ pensions “are slightly enough to buy salt,” as another migrant painter, Hunter Ge, told me.

“For the Chinese, especially in the countryside, there is no such thing as retirement,” he said. His grandfather is 90 years old and cleans up pig manure from a farm in the central province of Henan every day.

M. Ge left his village at the age of 17 and started working in structures and factories. He turned a profit during the six years he worked at Foxconn, a manufacturer contracted by Apple. But when he found himself unemployed this year, he lost his job. He can’t collect any unemployment benefits, which isn’t unusual because local governments are heavily in debt. Now 34, he still works 10-hour shifts at some other manufacturer contracted by Apple and lives in a dormitory.

On the morning of our conversation, I had just left a shift that at 7:30 p. m. He had worked for two weeks without a day off because of the call for Apple’s newest iPhone.

He feels like he’s moving from home to his village and doing nothing while his parents and grandfather are still working. “It’s just not appropriate,” he said.

Most of my interlocutors requested anonymity for fear of reprisals from the government. There is no doubt that they are better off and more aware of their rights than other migrant workers. Conversely, most rural dwellers are more secretive about their living situation than the other young people I interviewed.

“My ideal country is one where other people live in peace and prosperity, where there is food security, freedom of expression, justice, media capable of denouncing injustices and a five-day, eight-hour workweek for workers,” he said. Zhang, the unemployed welder. If those goals can be achieved, whoever is in power will do so, regardless of their party or the length of their government. “

The other truth faced by migrant workers is that returning to their villages to earn money through farming is an option, as Mr. Xi. Il has enough land waiting for them. That’s why they’re known as “surplus rural labor. “in Chinese official and educational discourse.

“Only other people who can’t find a task go into farming,” said Guan, a migrant employee from the northwestern province of Gansu, “because farm income is too low. “

Guan, 30, worked as a real estate agent in Shenzhen for five years before returning to his hometown in late 2019. It now operates bulldozers. He lives in transient tin house structures, works 10 hours a day, and is paid only for the days worked, about $50 a day, with no benefits.

You need to make as much money as possible while you’re young. He also knows, from his many teams of WeChat messages about the projects he is working on, that the number of structural projects is shrinking and that some of the staff are not being paid. He thinks, he might never come.

“To be honest, deep down I feel lost,” he said. “All I can say is that, for the time being, I will save as much cash as possible. As for what the long term holds, it’s hard to say. . He probably wouldn’t even live to that age.

Li Yuan writes the New New World column, which focuses on the intersection of technology, business, and politics in China and Asia. Learn more about Li Yuan

Advertising