“There is a bright future for our country, but achieving it will not be easy. We achieve our purpose with individual effort, nor can we realize our dream overnight. Every achievement in the world is earned with effort. The brighter in the long run, the harder we have to work for it.

Dragged out of his family’s home in his youth, the longtime Chinese president faced a crowd of angry revolutionaries.

“Down with Xi Jinping,” they chanted, and their own mother was forced to sign up for them.

Shortly after 1966, when Chairman Mao unleashed the Cultural Revolution.

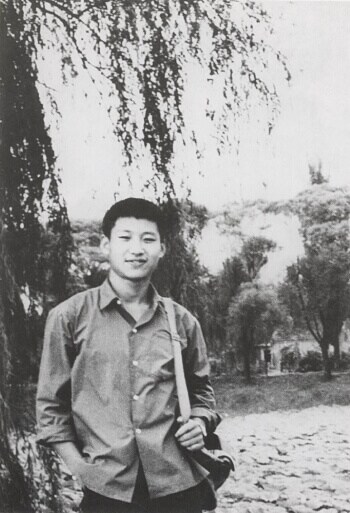

Until then, the young Xi Jinping had led a cloistered “red royalty,” the son of a revolutionary hero who fought alongside Mao.

He even studied at the August No. 1 Boarding School, as “Cradle of Leaders”.

But when his father, Xi Zhongxun, was accused of disloyalty, their lives were turned upside down. Student activists ransacked the circle of relatives’ homes and beat their father.

It was too much for Xi’s older half-sister, who probably committed suicide. Official accounts say she “chased to death. “

Mao ordered well-informed urban Chinese youth to live and paint in the countryside to undergo “re-education” through substandard peasants.

In 1969, Xi found himself in a backward rural village of Liangjiahe. At first, the grueling paintings were so insufferable to the soft-spoken, studious Xi that he ran away from his home in Beijing. He shot quickly.

In total, he spent seven years living in caves and managing the land.

“With this kind of experience, no matter what difficulties I encounter in the future, I am completely full of courage to take on any challenge, in the most unlikely, and triumph over obstacles without panicking,” Xi said later in 2002.

His previous 2013 speech, delivered shortly after coming to power, helped cement the story of Xi, now a central myth of his fashionable China.

Today, the village and caves in which Xi slept are a major tourist attraction, attracting patriotic travelers and the Party on “red pilgrimages. “

Xi is described as “still a son of huangtu” or “yellow earth,” a way of showing that he does, in fact, understand the price of sacrifice.

“The brighter the future, the more we have to paint for it,” as he said in 2013.

After the years in the desert, Xi was finally accepted into the Communist Party’s youth league.

From formative to young, he went from victim to unconditional fan of the Party.

Mao’s Cultural Revolution had worked.

The party made Xi “even more faithful to the cause, because he had been forced to doubt it very much,” said Joseph Torigian, an assistant professor at American University who is writing a biography of Xi’s father.

In the 1980s, Xi himself declared that he would once again dedicate himself to the people, to prevent the Cultural Revolution from receding.

For Xi, their suffering was a mandatory component of the Communist Party’s consolidation of China.

He would fight and nail never to let go.

“The Internet cannot be a position of anarchy. The use of the Internet to advocate for the overthrow of the government, pontificate devout extremism, or incite separatism and terrorism must be resolutely prevented and punished.

When a mysterious virus emerged in Wuhan in late 2019, Chinese Communist Party censors went into overdrive.

Interestingly, all mentions of the city’s hospitals, waves of infections disappeared from the Internet, almost instantly.

Offline, other people were also censored.

Dr. Li Wenliang, who tried to warn his colleagues of the initial infections, was quick to punish. He subsequently died of coronavirus.

Those who sought to narrate the anguish of mass deaths and demanding situations of home isolation forced to disappear.

Even today, other people warn of new blockages.

China began experimenting with Internet censorship in the early 2000s. Its allocation of Golden Shield allowed the government to gain and send all knowledge and block websites, adding, in 2002, Google.

But gradually, the online space part has loosened to allow bloggers and social media to thrive. This gave other people the strength to criticize government officials and organize among themselves.

Xi temporarily suffocated him.

In a leaked speech in August 2013, Xi warned that “the Internet has the main battlefield in the struggle of public opinion. “

Behind today’s so-called “Great Firewall of China,” even Winnie the Pooh has been caught in the crosshairs of Xi’s tight control.

In 2013, a symbol comparing Xi and President Obama circulated online at a summit in Pooh and Tigrou.

It’s too much for China’s strongman. Government censors erased mentions of the burly bear from the web more or less forever.

Rare photographs of the now are a sign of silent defiance.

Two months before Xi’s speech earlier, he made an “inspection tour” of Chinese state media, not easy “absolute loyalty” to him.

Since then, China has had the world’s worst newshound jailer for 3 consecutive years, according to an annual review by the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Xi has also built a complicated virtual surveillance state.

Facial popularity cameras are now ubiquitous, as is biometric identification, to track what other people are doing, where they are going, and what they are buying.

Some of this knowledge fuels China’s fledgling “social credit system,” a program designed to praise what the Party considers a “good” habit and punish others for things like garbage. Misbehavior can result in the revocation of certain privileges, such as airline ticket acquisition and exercise.

All corporations operating in China, Chinese or foreign, are required by law to hand over knowledge to the state upon request.

The government even partly owns Chinese global tech giants like ByteDance, the owner of TikTok, raising questions about users’ knowledge around the world.

Rare demonstrations are still organized in defiance of censors in China.

But they are temporarily silenced by the authorities, or more detained at the level-making plans while others try to organize online.

Xi might want a “healthy internet,” but not one that risks giving the other 1. 4 billion Chinese a chance to share their grievances.

“China’s socialist democracy is the broadest, most authentic and maximally effective democracy in safeguarding the basic interests of the people. [. . . ] We will have to rigorously shield ourselves and take resolute measures to combat all acts of infiltration, subversion and sabotage, as well as violent and terrorist activities, ethnic separatist activities and devout extremist activities.

A year after that speech, Xi removed presidential term limits.

The two-term limit set in the 1980s to save you too much strength from being in the hands of one man.

In October, Xi is expected to be the country’s first leader since Mao Zedong to rule for a third term.

Since Mao, China has looked so authoritarian.

In his three-and-a-half-hour speech to launch a momentary term in 2017, Xi made it clear that China’s Communist Party is the only political system.

The formula is a canopy to burden all freedom of expression and civil society.

Xi’s crackdown began as soon as it gained strength with an “anti-corruption” campaign, longer and deeper than that of any of his predecessors.

It has been hailed as a way to plug endemic grafting.

But it has temporarily become transparent that Xi also cleanses China of its political opponents.

Watch below for a trailer of our new podcast: How to Become a Dictator

In recent years, it has prolonged its repression, or anything, that is seen as a challenge to the strength and authority of Xi and the Communist Party.

Human rights lawyers have been imprisoned. Dissidents are space arrests. Many are tortured and forced to confess before closed trials.

Celebrities and billionaires who are too tough or too popular have found themselves increasingly silenced or disappeared.

China’s richest man, Jack Ma, and tennis player Peng Shuai are among those missing for defying authorities. Or they reappeared later pledging allegiance to the Communist Party.

Meanwhile, Peppa Pig, the popular British character, has been deemed “subversive,” a sign of Xi’s anxiety about too much foreign influence.

Similarly, men considered too effeminate can no longer participate in television programs.

And under Xi’s supervision, disrespecting the national anthem can mean up to 3 years in prison.

Most frightening of all is Xi’s crusade to wipe out the Uighurs, a predominantly Muslim ethnic minority living primarily in China’s western Xinjiang region.

More than a million Uighurs and Muslim minorities have been detained in internment camps for “re-education. “Many have since been sentenced to decades in prison.

Some have been arrested for what China considers criminal activities: praying at home, growing beards or contacting others abroad.

Former detainees told The Telegraph how they were locked for days in “tiger chairs”, a torture used for interrogations.

Others were electrocuted with farm animal batons, given white pills to sterilize and swore allegiance to the Party.

They were forced to pay the cost of their “re-education” after months or even years of detention.

The women also told The Telegraph about sexual abuse, rape threats and beatings in the womb.

The British parliament and the U. S. government, among others, have called it genocide. The United Nations has claimed that “patterns of torture or ill-treatment, including forced medical treatment” would likely amount to crimes against humanity.

Beijing insists its program is designed to reform “terrorists. “

But all this is intolerance towards cultures and other people who do not conform to mainstream Chinese society, and an intense concern of separatist movements.

Pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong and militant priests in Tibet have also been branded as terrorists.

Xi’s repression is spreading around the world.

Frankish Chinese citizens abroad find their loved ones taken hostage at home in an attempt to silence them. Activists are also monitored abroad and interrogated upon their return, and police show them photographs taken abroad.

Five Hong Kong-based men, a Swede and a Briton, connected to a publisher selling books banned on the mainland, were kidnapped overseas.

Smuggled back to China, they gave the impression on state television of making forced confessions.

A recent Telegraph investigation found that China operates “overseas police stations” in London to track other people and “persuade” them to return home.

Some Chinese liberals hoped things would be different with Xi, a guy who had lived and worked in America and whose daughter had gone to Harvard, albeit under a secret name.

Today, even vegetarianism has been criticized for Western attitudes.

“The basic purpose of the Party since its founding, to unite others and guide them in revolution, structure and reform, is to give them a better life. Always put others first.

Xi has long characterized himself as a man of the people.

His difficulties in exile from the Cultural Revolution have become the basis of the cult of personality he built.

“I know what poverty is like,” he said in his annual speech in 2022.

Images abound in state media of him surrounded by smiling young people and world leaders: academics and farmers. A guy respected by all.

His symbol is also on billboards across the country and will need to be displayed in every place of worship, from temples to churches.

Students as young as five will now have to be informed of Xi Jinping’s idea in schools.

Party officials and public officials will also be required to “vet Xi” through a mobile app or as part of mandatory categories in schools. Universities have established institutes of study to examine doctrine.

In the “red” sites – he puts the history of the Party – it is not uncommon to see rows of bureaucrats in matching uniforms, sitting on portable stools, listening to long lectures about Xi’s arduous adventure to the most sensible and his devotion to the people.

But the emphasis on loyalty can backfire.

There is little incentive for the Party to report mistakes at the top of the chain, for fear of wasting the next promotion. The result is a series of disastrous cover-ups, as observed in Wuhan.

Those who can have migrated under Xi, a trend that accelerated after experiencing the world’s most draconian coronavirus policies.

The “zero covid” enforcement meant that, in some cases, cameras were placed inside people’s homes to make sure certain quarantine rules were met, while staff headed to spray disinfectant.

It is no longer just dissidents, who are seen as a risk to the Party, who are under constant surveillance throughout the state.

References to Xi as the “main” leader imply that he seeks prestige similar, or impressive, to Mao’s.

But even though Xi’s state is at the center, very little is known about him and his family.

His daughter, Xi Mingze, is almost never photographed and his first wife, believed to live in the UK, has been removed from her official biography.

The influence of his mother, who some say played a role in advancing his career, has also never been revealed. It is known how many siblings he has.

Behind the propaganda, an undercover source told U. S. officials that Xi was “exceptionally ambitious” and had an “eye on price” from the start.

A U. S. diplomatic cable Leaked U. S. Immigration Administration in 2009 says it doesn’t seem to care about cash at all, but that it can only be “corrupted through power. “

“A Cold War mentality can only alter the framework of global peace, hegemonism and force politics can only endanger global peace, and confrontation between blocs can only exacerbate security threats in the twenty-first century. We will have to respect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries. , [and] oppose interference in internal affairs. . . ‘

Xi becomes the statesman in a speech earlier this year, calling for global stability and security and countries to resolve their differences.

But its first ten years in force tell us that it is willing to threaten everything for the final price: Taiwan.

China’s leaders have long made transparent their intention to take over the island, with its own elected government, military, currency and foreign policy, which Beijing considers a renegade province.

But it was Xi who specified a timeline: until 2049, to achieve “national rejuvenation. “

Xi has already turned China into a military superpower, upgraded its weapons and publicly called for a record number of troops to be “combat ready. “

Last year, reports emerged that China fired a nuclear-capable missile from a vehicle traveling at hypersonic speed, at least five times the speed of sound and with enough force to circle the globe.

If this is true, China would have demonstrated a complex capability that no country has achieved before. America is striving to catch up.

Since Xi came to power, military spending has seen the most powerful expansion of any major country.

China’s sovereignty also happens to be expanding under Xi.

The military dredges the South China Sea to build synthetic islands, which Beijing is militarizing in defiance of regulations on foreign waters.

In Kong, armed police crushed a pro-democracy movement. A new “national security law” has prolonged Beijing’s full control over the former British colony, ignoring the move agreement.

The patchwork of surveillance technologies of Chinese corporations is now exported overseas. China will dominate 5G, synthetic intelligence and facial recognition, raising fears of a large collection of knowledge.

Many countries are also being cultivated thanks to Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The $1 trillion global network of ports, railways, roads and infrastructure that Chinese power is leaking into 140 countries around the world.

Poorer countries borrow heavily on unfavorable terms, forcing them to cede control of very important assets to Beijing.

Take, for example, the key port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka, now bankrupt.

China has a 99-year lease and this year welcomed a Chinese shipment that Washington and New Delhi feared could spy on neighboring India.

Belt and Road investments have even reached the UK: a freight rail line linking the port of Yiwu in China with a Barking station in London opened in 2017.

This boost to its influence abroad is connected to Xi’s “Chinese Dream,” a commitment to repair and rejuvenate China and its position in the world, to make China wonderful again.

Xi believes his dream can help regain what was lost in the “century of humiliation,” in which he fought in the opium wars with Britain.

“China has been reduced to a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society and has gone through an era of suffering worse than ever,” he said last year.

Celebrating the Party’s centenary, he said “we will never allow any foreign force to lie to us, oppress us or subjugate us. “

“Anyone who tried to do so would have their head slain with blood in opposition to the Great Iron Wall through more than 1. 4 billion people. “

We depend on advertising to fund our award-winning journalism.

We urge you to disable your ad blocker for The Telegraph’s online page so that you can continue our quality content in the future.

Thank you for your support.